Didn't like it?

Then look again.

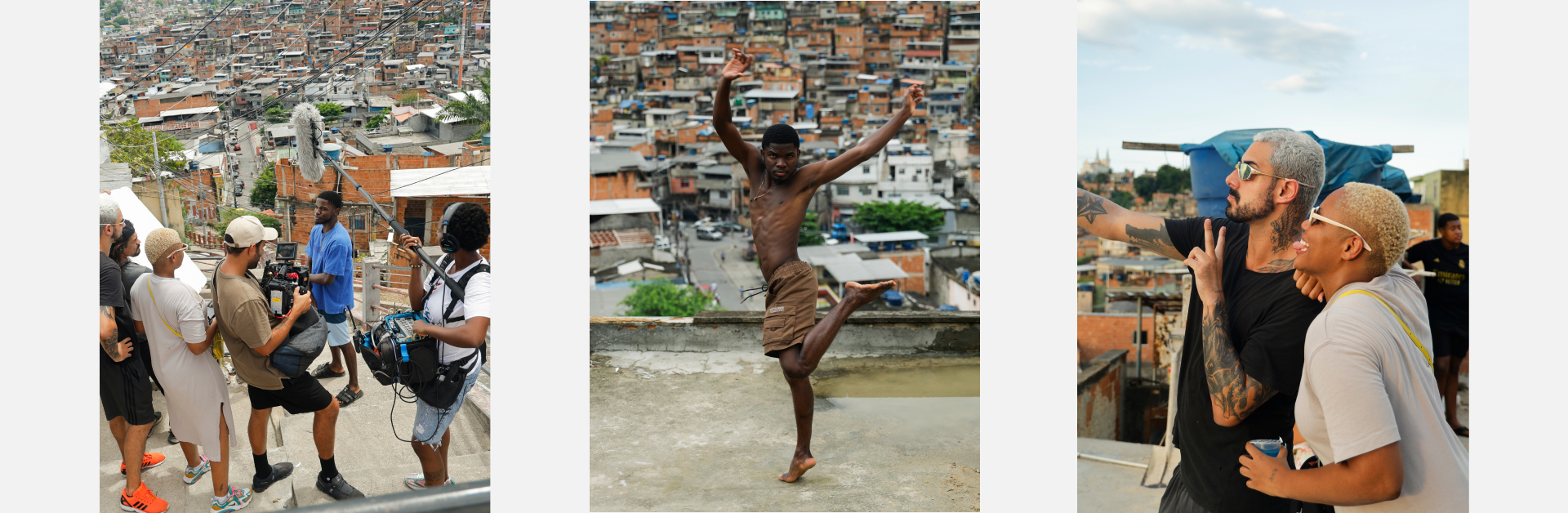

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

When diving into the research to direct the documentary Passinho Foda - O Corre por trás da Dança, it became clear from the start that this wasn’t just about documenting a movement, but about establishing a dialogue with a living cultural expression. These young artists who dance at home, on the rooftops, at the parties, and in the battles are not just characters of a past story – they are the authors of the present. Watching how those who created the movement years ago are now reaping the rewards of work built with effort and dedication is something powerful and inspiring.

In the beginning, I had a fear: could I, with an outsider's perspective, without a carioca accent and not being part of the funk universe, tell this story in a legitimate way? But fortunately, that fear dissipated in the first few days.

Telling stories is a right – as long as it’s done with respect for those who grant the privilege of sharing them.

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

It was with that mindset that my friend and co-director, Fred Ouro Preto, and I made a crucial decision:

We didn’t want to make a film about Passinho, but with Passinho.

Locking ourselves in a room to write a script wouldn’t make sense. The best ideas came from the streets, the rehearsals, the conversations, the parties, the laughter—and even the clashes that came before anything was put on paper.

In those exchanges, one understanding became clear: behind the fast, complex footwork, the body awareness, and the physical strength, there was a simple truth—at the beginning, the goal was just to have fun and be seen at the parties. But in the favela, fun is never just fun. It becomes a political act. With every new move created, with every crew formed, an existence is reaffirmed: "we are here."

Passinho never asked for permission to exist. It simply took up space. First at the parties, then in the streets, and soon after on TV screens, in films, and across social media. And in doing so, it revealed something essential about society: it consumes Black culture, but often denies dignity to its creators and their art.

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

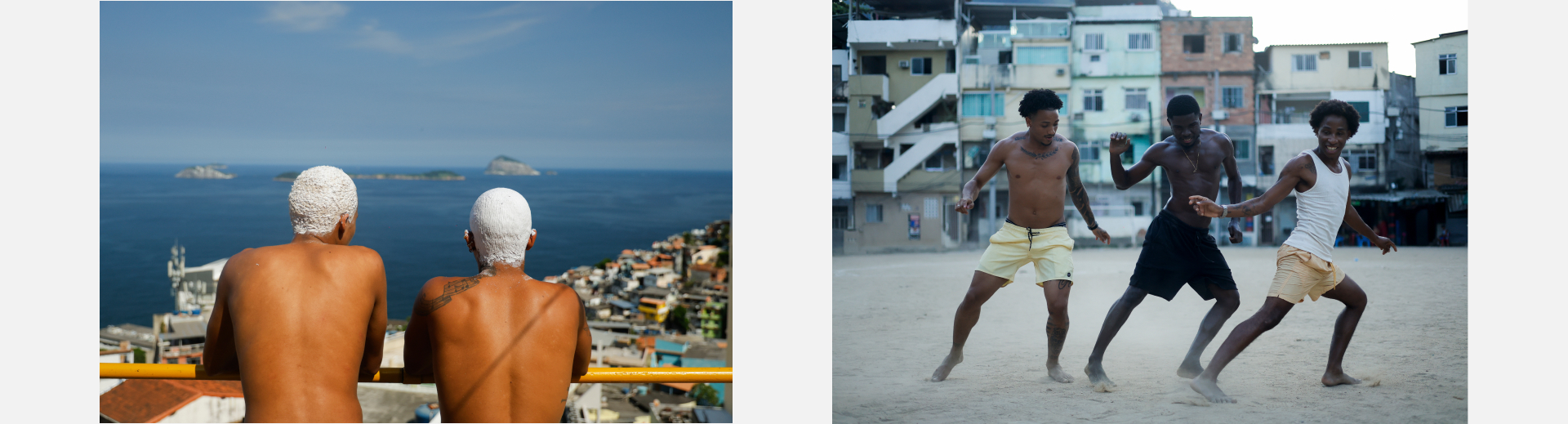

"You don’t like my body? Then I’ll dance, and I’ll dance so well that I’ll make you like it and still have you applaud me." – Pablinho Fantástico

Perhaps what moves me the most about Passinho is this ability to turn rejection into fuel. "Didn’t like it? Then look again" – that seems to be the philosophy. Passinho rewrites the rules and breaks barriers. While filming, we weren’t just capturing dance steps; we were documenting a new chapter of cultural resistance in Brazil.

Funk and Passinho carry an ancestral logic: what begins as an expression of joy soon becomes a tool for symbolic survival. Just as synchronized rituals in the past were used to intimidate predators, funk parties challenge marginalization by occupying spaces with moving bodies. The euphoria of the dance explains part of the compulsion for movement, but the social impact goes beyond that – a community is built that, through synchronicity, affirms: "we exist, we create, and we will not be erased."

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima

Just as our ancestors discovered that synchronization transformed fragility into collective strength, Passinho is born from that same principle. Periphery youth, in a context that vulnerabilizes them, turned individual and collective steps into art – and into a synchronized political body.

In the end, there was the certainty that Passinho is bigger than any film. It is a living language, a memory in motion.

Photo by Marcos Serra Lima